Apr 22 - May 21, 2017

Press Release

Whitebox Art Center is pleased to announce the exhibition, “Graces of My Heart – Chen Wenling’s New Works” opening on April 22, 2017. This exhibition is academically hosted by Mr. Fan Di’an, and curated by He Guiyan. Considered to be Chen Wenling’s most important solo exhibition in recent years, the show presents five new sculptures and drawings from the last decade.

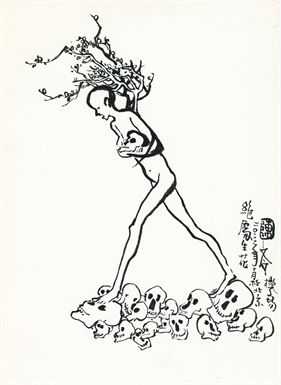

Chen Wenling’s new works are formally relevant to an earlier period of his art practice, while the essential impetus of sculpture making has departed. His earlier works maintained a dialogue between the artist and the context of his time. In his recent works on the other hand, the artist shifts to an approach that adoptsthe personal narrative, articulating the artist’s visual representation on the understanding of life. Walking Manportrays a slander man wearing a gasmask, carrying peach blossom on his back, and embracing a crystal-like object, to conveythe artist’s new realm of understanding on art practice as part of life. The gasmask is an allegory for the pain brought by social symptoms, and the peach blossom on the man’s back symbolizes the lyrical and determination in a chaotic environment of decay – the work is undeniably Chen Wenling’s personal narrative in returning to one’s own experiences.

Over the last decade, other than his focus on making sculptures, Chen Wenling has accumulated over thousands of drawing and sketches, a way of releasing emotion in times of solitude. These works comprise of the various aspects he has observed in art and life, as well as his wild imaginations. Through his liberal depiction of one’s true sentiments, he discovered the rare moments to breathe smoothly as he translated his ideas between the two mediums: sculpture and works on paper, while they embody the artist’s unsung diligence throughout his artistic career. This exhibition presents for the first time, 200 meticulously picked drawings.

The curator of this exhibition, He Guiyan considers Chen Wenling to be an artist working with unique style in the field of sculpture. The presentation of his sculptures and drawings he had made over the years allow the viewer to review the chronology and diversity in his art practice. Resonating with the high ceilings and architectural features of the Whitebox Art Center, the exhibition provides a great opportunity to revisit Chen Wenling’s academic contribution to the field.

This exhibition is artist Chen Wenling’s first collaboration with Whitebox Art Center, and we hope our visitors will come and experience the artist’s new works. The exhibition will continue until May 21, 2017.

Curator Article

Diversion: Chen Wenling’s Sculptural Practice

Text: He Guiyan

Since the early 1990s, a critical diversion in contemporary sculpture occurred based on its ontological realm, aimed at translating its artistic language into the contemporary. In this process, not only has contemporary sculpture shown “pseudo-sculpture” tendencies, or an affinity to the characteristics of installations, moreover, in the pursuit of conceptual expressions, it was influenced by the Chinese avant-garde. The other change is marked by the sculptors’ emphasis on their intervention to reality in general, focusing on the relationship between the work of art in relation to the external social and cultural context. In the late 1990s, contemporary sculpture entered a phase of diverse development, where urban sculptures burgeoned, deconstructive works and feminist works emerged, of which the body, issues on identity and gender became the new subjects in creative discourse. Chen Wenling’s Red Memory was outstanding, and drew attention of the art world. The playful approach and iconic presence revealed the artist’s distinctive individual style.

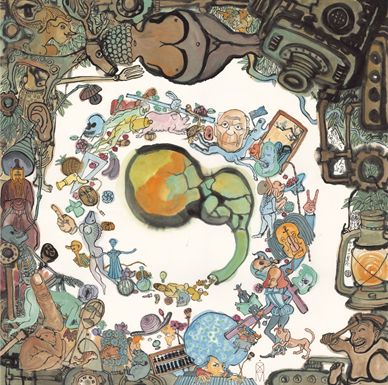

In the post 2000, the linear narrative in contemporary sculpture waned, while its semiotic diversion was yet to be completed. For most contemporary sculptors, how to assign “contemporaneity” to the works of art was still critical. Certainly, in practice, the artists’ approach of solving the issue of “contemporaneity” varied. Some emphasized on the logic of sculpture making inherent in China, others enforced the subtle “Chinese identity” in their work, some hoped to challenge the existing boundaries of sculpture making by means of new media or using readymade materials, others returned to the traditional sense of aesthetics. With the examples of Happy Life and God of Materialism, Chen Wenling’s emphasis on social parameter, the relationship between the work of art and its time, reality and the condition of contemporary existence was apparent, moreover this series of works was posited in the social discourse of inflated consumption. In the consumer era, a critical characteristic is “materialism”. French philosopher, Charles De Brosses created the term “fetishism” in 1757. In his research, he discovered as early as the primitive society, “fetishizing” behavior had already existed. In order to expel fear, the primitive man personified the power of unknown objects, assigning a mysterious power to “objects”, by which to prove one’s own existence; “Fetishism” is the ritualization and indoctrination of peoples’ “fetish” behaviors. In the Marxist view, “material fetishism” equally demonstrates a unique cultural psyche that considers owning consumer goods symbolic of wealth and value. Therefore, the consumer goods equally possess a mysterious appeal, stimulate people to be infatuated and venerate them. By adopting a playful, satirical and exaggerated approach, Chen Wenling enhances the powerful energy that “fetishism” produces, one that originates in the individual’s conflating desires. On the one hand, “fetishism” unequivocally “materializes” people, on the other hand, under the insurmountable pressure of one’s desires, people become mad or even lose the sense of self. Thus in the course of consumption, possession, enjoyment, desire devours reason, infinitely peeling off the layers of humanity, only leaving behind its naked animal instincts. In fact, these obese, voluptuous and inflated bodies are true portrayals of the truthfulness of existence, while act as visual representation of a conflated desire. The rich colors further enhance the visual appeal of the artworks. In fact, rich colors have a critical origin, for which the artist drew inspirations from the commemoration Hakka cultural custom – often understood as glamorous and ceremonious, extravagant and ritualized. This kind of visual experience drawn from the local, folk, and inherent culture, as well as its cultural psyche have been critical in Chen Wenling’s art practice.

Around 2009, in the field of Chinese contemporary art, a wave of “returning to tradition” was prevalent. The reason “tradition” regained general attention in the art world was in one way, under an expanding global discourse, China was urged to reexamine its cultural identity and subjectivity as a nation, at the same time, it synchronized with the cultural development agenda of the nation since 2000; in another way, a more profound drive to search for a return to and diversion from tradition in contemporary art practice was the encounter with a looming inner crisis in the narrative discourse of contemporary art. Confronted by it, we had to reflect upon the course of development in contemporary art, the cultural and artistic pursuit of various periods over the last two decades, while consciously moving away from the contemporary art apparatus dictated by the western standard and “post-colonial” taste in order to rebuild the critical parameter and value standard. For the artist more importantly, their work lied in formulating the indigenous, oriental, individual visual repertoire.

During this period, Chen Wenling created the China Scene series. For instance, works such as, Happy Life and What You See is not Necessarily True, the artist’s work focused on the sociological narrative, highlighted through an affinity to realism. Then, works such as Chinese Landscape, Making Gardens, marked the artist’s transition in the logic of artistic language, where the pursuit of aesthetic taste proceed the content. China Scene created a visual phenomenon with its enormous scale, and the reflexive function of the stainless steel produced visually compelling effects. At the same time, mediated by “looking”, the work not only has kept a distance with the viewer, but also comprises of a certain “dialogue” relationship. The overall impression of the work is inherent of the oriental aesthetics, rich in lyricism. On a microcosmic level, there are various compositional elements in the work of art, however the artist has weakened their inference to reality, containing them to the round, fluid expression of linear language. Those flowing, integrated visual language enforces the continuous aesthetic impression, adding a sense of movement and time to the work. It is apparent that Building the Garden literally represents an oriental taste. Moreover, the work has another aesthetic dimension, which is “theatricality”. In other words, between “making the spectacle” and “viewing it”, the time and physical presence of viewing constitute as part of the artistic expression. In fact, in the art wave of “returning to tradition”, the ways in which the artists approached it were diverse, some took the formal and linguistic path, some emphasized on the translation of motif and concept, some focused on the invention of methodology, and others paid attention to the oriental identity embedded in form. In the field of contemporary sculpture, a period in which Chen Wenling’s impressionistic rhetoric and the pursuit for oriental taste allowed him to be exceptional.

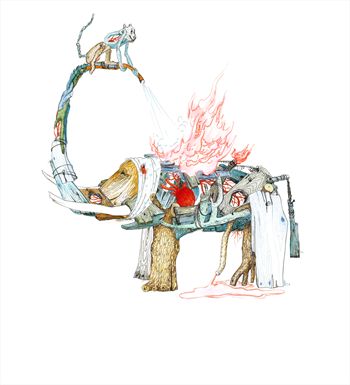

Visual spectacle became a direction in which Chen Wenling steered towards, in works such as Arc of Transcendence and Inner Sense, the artist has not only created the wonders of a visual world, but also asserting a narrative to the works. For instance, in the course of making Arc of Transcendence, Chen was not concerned with the accuracy to the legendary story of “Noah’s Arc”. Instead he hopes to represent a world where the real and the surreal, the naturalist and the illusions converged. Rather than believing Chen Wenling’s intent was to tell the story of Noah’s Arc, his expectations lied in the meaning engendered from the language and narration of sculpture making. Even from the point of view of linguistic departure, the work is exemplary of the artist’s exceptional imagination.

The exhibition presented at the White Box Art Center is a partial presentation of Chen Wenling’s sculpture works from the last three years, accompanied by hundreds of drawings and sketches. While these sculptures are formally relevant to his earlier works, the essence and creative notion have since shifted directions. Whether Happy Life series, or the What You See is not Necessarily True, they are related to the time the artist lives, the life around him, and people’s mental conditions. Being sensible to the changes of the time, concerned with people’s state of existence, Chen Wenling is keen on capturing the cultural experience of the present. Thus these works embody the artist’s rich realistic impressions. However, his new works focus on the experiences that are personal, physical and his inner life, this marks an inward transition, one that is as concerned with the social and cultural phenomenon of the outside world as the individual’s existence. It is also a transition that marks the shift from cultural to physical experience. In the face of confronting death, Chen Wenling did not surrender, instead his continuous inner dialogue, sensibility for the most truthful desire for life, as much as his body and spirit were subjected to tremendous pain his courageous confrontation helped him to find solace in his artistic practice. The “Graces of my heart” is not a reference for any artistic style, but the artist’s enlightenment about life and art – that draws from the suffering in life is rewarded by it. It presents a state of existence, or a transcendental and lyrical realm of life. For instance, Walking Man portrays a slander man wearing a gasmask, carrying peach blossom on his back, and embracing a crystal-like object. As an iconic reference, the gasmask is an allegory for the pain brought by social symptoms, although he stumbles along, the crystal clear object continues to illuminate him on his path ahead, and he peach blossom assigns lyrical qualities to life, filling it with romance.

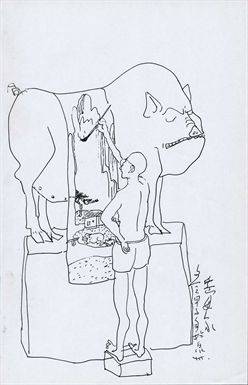

Of course, in the sculpture works made in the same period, we can equally discover the progress Chen Wenling has made in terms of his artistic language and narrative. Among them, we do not find any institutional trace, neither have they moved forward relying on the language’s inherent logic, instead they are more inclined to Chinese folk and popular visual experiences. Their compositions are comparable to the representation of legendary figures and stories found in temple fairs, park activities. Through such playful and witty expressions, the narrative mode in these works seemed to share affinity with painting.

Over the last decade, other than his focus on making sculptures, Chen Wenling has accumulated over thousands of drawings and sketches, an artist’s way to release emotion in times of solitude. These works comprise of the various aspects he has observed in art and life – some reflection on reality, on personal memories, others documented his truthful realization about life, as well as his wild imaginations. These are not serious works of art, but in the contrary, serve as a visual diary, or as visual fragments that document and testify for the artist’s journey of the heart. Unconfined to any singular form or modes of representation, these works vary from sketches, ink painting, illustrations, or even animation. Most of the time, the artist executed them forthright, liberally depicting his real feelings beyond sculpture making. Moreover, through the conversation between sculpture and works on paper, Chen Wenling enjoys the restfulness and sense of freedom art practice has provided him. Sculpture and painting, reflexive of each other, converging to provide same outcomes in spite of their differences. In fact, in the artist’s own words, diversion is perhaps the common phenomenon. But for the critics, we are more interested in the opportunities that propelled the change.

April 15, 2017

Sichuan Fine Arts Institute